In Kyrgyzstan, Russia’s all-out war against Ukraine has inspired a reexamination of the Soviet Union’s violent legacy. For some, this process began decades ago, with the advent of Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of Glasnost. But more than 30 years after Kyrgyzstan gained independence, it remains an uphill battle. Though the war may have strained ties between Bishkek and Moscow, public criticism of the former metropole remains taboo. Meanwhile, initiatives aimed at amending Kyrgyzstan’s law on rehabilitating victims of Soviet-era repressions and declassifying relevant archives appear to have stalled. According to local historians, however, people are looking to the past for answers nonetheless. Freelance journalist Charlotte Delmas reports for The Beet.

I find Bolot Abdrakhmanov waiting for me with a smile on his face that almost reaches up to his midnight blue cap. “I’m always happy to talk about my work when people are interested in it,” he says. The place where he has arranged for us to meet is the Ata-Beyit memorial site, a literal result of his work, which forever changed the perception of Kyrgyzstan’s past.

Ata-Beyit, meaning “grave of our fathers” in Kyrgyz, is a memorial to Kyrgyzstan’s victims of Soviet-era repressions, located about 20 kilometers (12 miles) from the capital, Bishkek. To reach it, we have to pass through a large arch that’s supervised all day by two guards, who appear unaccustomed to seeing people visiting this solemn place. Located at the foot of a mountain range, the memorial complex overlooks the village of Chon-Tash, where Kyrgyzstan experienced some of the darkest hours of Joseph Stalin’s terror.

Abdrakhmanov discovered this place’s story more than 30 years ago, somewhat by chance. During the Gorbachev era, when he was an officer in the Kyrgyz KGB, he met a resident of Chon-Tash, Bubyira Kydyraliyeva, who said she was carrying a dark secret. “She kept silent all her life, and during the Perestroika period she finally agreed to tell me her secret,” Abdrakhmanov recalls. Kydyraliyeva’s father, who worked in the village’s old brick factory before taking a job as a caretaker at a local KGB dacha complex, had told her the location of a mass grave filled with victims of Stalin’s purges.

Abdrakhmanov immediately sought to launch an official investigation, despite the objections of his superiors. As a result, in 1991, the authorities discovered 138 bodies buried at the site between 1937 and 1938. They were later identified as members of the Kyrgyz political and cultural elite who had been accused of being “enemies of the people” (only one body could not be identified). “It’s quite ironic that a KGB officer revealed this story,” Abdrakhmanov jokes sadly, looking away from the factory.

The Ata-Beyit memorial was created in 2000. The victims’ remains now lie beneath a monument in the shape of a tunduk, the circular apex of a traditional nomadic yurt.

Abdrakhmanov turned to research more than a decade later, in 2013, applying to a PhD program in history at Bishkek’s I. Arabaev Kyrgyz State University. Thanks to his past service in the KGB, he was allowed to access the national archives and, in 2021, he published a 10-volume Kyrgyz-language work documenting Stalinist repressions. Now retired, Abdrakhmanov has only been able to publish 10 sets of his books, which list some 20,000 victims. He never received any state funding to support this titanic undertaking.

Blurring the lines of history

Over the years, Ata-Beyit has been transformed into a “memorial complex” crowded with monuments dedicated to a variety of historical events. A monument built in 2016 commemorates the Great Urkun, the 1916 Central Asian uprising against Tsarist conscription and the subsequent mass exodus to China. A few meters on, we’re propelled into 2010, to a cemetery for the demonstrators killed during the Second Kyrgyz Revolution. Last September, some of the Kyrgyz soldiers killed during the border conflict with Tajikistan were interred here, as well.

For independent scholar Asel Doolotkeldieva, the superimposition of all these places of memory “blurs the lines” of history and embodies the vagueness of Kyrgyzstan’s haphazard memory policy.

“There may be many other execution sites like Ata-Beyit in Kyrgyzstan, but we may never know,” Abdrakhmanov says. Records from the KGB archives are still classified, he explains, half-heartedly deploring the lack of resources allocated to young historians in Kyrgyzstan.

Past attempts to correct this have fallen flat. In 2019, 16 lawmakers put forward a bill aimed at amending Kyrgyzstan’s law on the rehabilitation of victims of the Red Terror and Stalinist repressions, and declassifying relevant archival records. But nothing came of it. A smaller group of parliamentarians proposed a similar piece of legislation in December 2022.

“We […] want our fathers and grandfathers to receive a proper historical assessment, and for future generations to receive reliable information about them,” Janarbek Akayev, one of the lawmakers behind the new legislation, told RFE/RL’s Kyrgyz service in January.

More than six months later, the bill is still in the public-discussion phase. And confronting the legacies of past repressions doesn’t seem to be high up on the political agenda — perhaps because Kyrgyz officials are still keen on maintaining good relations with Russia amid its war against Ukraine.

The Kyrgyz authorities have become openly disenchanted with journalists and activists who discuss the war, and the state is now unwilling to allow any public criticism of Russia. For months, the security services have been actively pressuring those in Kyrgyzstan who support Ukraine too overtly.

Human rights activist Gul’shair Abdirasulova reported that plain-clothes officers in Bishkek detained at least five people who came to lay flowers at a war memorial on February 24, the anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion. In March, 24.kg journalist Gulmira Makanbay received a warning from the security services after she published an interview with a draft dodger from Buryatia who said the war had fueled support for the republic’s independence from Russia. According to Makanbay, intelligence officers told her that the subject of the interview “could negatively affect future relations” between Russia and Kyrgyzstan.

Russian anti-war activists Yulia and Ilya Kuleshov, a couple who have been living in exile in Bishkek since February 2022, regularly hosted discussions on topics such as decolonization, Kyrgyz culture, and LGBTQ+ rights as part of a project known as Red Roof. The Kuleshovs shut down the project on March 23, citing mounting pressure on the émigré community; the security services, they said, had threatened them with deportation to Russia.

In early June, RFE/RL’s Kyrgyz service reported that at least three Russian anti-war activists had been arrested in Bishkek in the space of 10 days. Two of the activists, Alyona Krylova and Lev Skoryakin, received jail time. The third, Alexey Rozhkov, was deported to Russia, where he faces felony charges for setting fire to a military enlistment office to protest the war against Ukraine.

The bridge of memory

On the margins of the state, Russia’s image is being deconstructed nonetheless. Experts say that decolonial studies are on the rise in Kyrgyzstan. “The return to memory is intimately linked to the process of decolonization, through which we intend to question universal knowledge and apprehend our history, culture, and language,” Kyrgyz historian Elmira Nogoibaeva said at the opening of On the Bridge of Memory, an international history conference held in Bishkek in March.

Nogoibaeva heads the research organization Esimde (“I remember,” in Kyrgyz), which organized the conference. Over the course of three days, researchers, historians, activists, and artists discussed the place of memory in former Russian colonies. “Our history is still very Moscow-centered,” Nogoibaeva explains. “That’s why we need to return to memory, in order just to know better who we are.”

These reflections aren’t just occurring at the academic level. Esimde seems to embody a recent surge of popular interest in looking to the past to understand the roots of modern-day Kyrgyzstani identity.

The organization’s initiatives mix historical research and activism, and it regularly organizes events — in the Kyrgyz language, of course.

One of its biggest projects has been to build an open archive of people who were persecuted during the Soviet era. Nogoibaeva says she has observed an increase in interest in this data collection since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. “People come to us and consult archival documents now. Many of them also find their ancestors in the dozens of volumes published by Bolot Abdrakhmanov,” she says.

According to Doolotkeldieva, it’s undeniable that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine was a “weakening event” for a certain part of Kyrgyz society. “The horrors committed in Bucha have made many people aware of what the Russian army can do to those who do not consent to the Russian imperial narrative,” she says.

Kyrgyzstan saw a massive influx of Russian draft dodgers after Vladimir Putin announced a mobilization drive in September 2022. Although they were mostly welcomed in Kyrgyzstan, some of these so-called relokanty (“relocaters”) have been strongly criticized on social networks for their condescending attitude towards Kyrgyz people and complaints about the infrastructure and services available to them in Bishkek.

For some, this neo-colonial attitude brings back memories of past sufferings. “I really see that ordinary families are starting to talk about how they were considered and treated as secondary citizens during the Soviet [period], how their parents were repressed at work or within the ethnic communities,” explains Doolotkeldieva.

At the same time, Nogoibaeva admits that decolonization remains a sensitive topic in Kyrgyzstan. There are still few researchers specializing in the subject. In March, a student at the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek said that faculty criticized and pressured her to change her thesis topic after she chose to research “decolonial discourse in Kyrgyzstan.”

“Over the past 70 years, a fear has developed, because in Soviet society we often talked about the victories, about industrial achievements. But we didn’t talk about the price the people paid or the fear of being killed. However, people are still afraid,” Nogoibaeva explains.

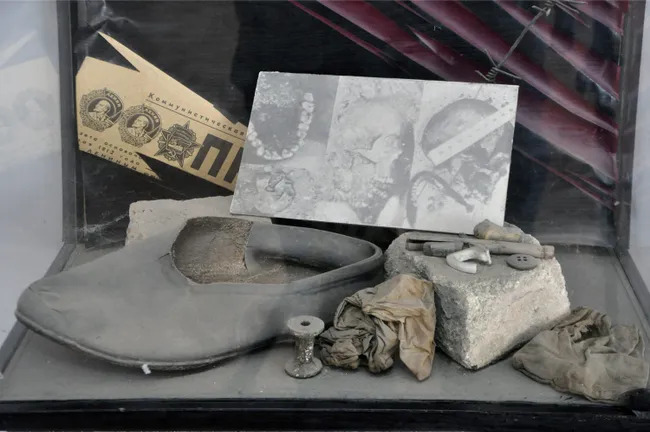

Indeed, Kyrgyzstan’s bridge of memory is still being built. Looking at Ata-Beyit’s small museum dedicated to the site’s victims of Stalin’s terror, Abdrakhmanov makes clear that he sees this as vital work. “Even if there’s no enthusiasm from the state, even if nobody gives us grants or says ‘good job,’ we’ll continue to build museums. We have to,” he concludes.

Source : MEDUZA